“In May of 1940 the public, the editors, the officials of the United States were thrown into utmost confusion by developments in Europe. Hitler had overrun quickly most of Western Europe. He had demonstrated furious and unanticipated striking power. The other countries had demonstrated weakness that was unexpected and unaccountable. Men lost their confidence in everything from seeing the nations of Europe go down so fast before Hitler’s armies.”

– The Reminiscences of Robert H. Jackson. Harlan B. Phillips ed.,1955. Columbia University, Oral History Research Office. pg. 881

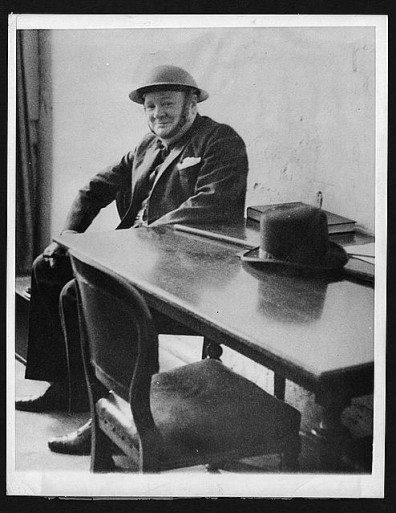

Winston Churchill had recently assumed the premiership of Great Britain when, on May 15, 1940, he sought assistance from the United States. Churchill’s May 15 cable to President Roosevelt described the dire situation that England was in.

“The scene has darkened swiftly. The enemy have a marked preponderance in the air, and their new technique is making a deep impression upon the French. I think myself the battle on land has only just begun…The small countries are simply smashed up, one by one, like matchwood. We must expect, though it is not yet certain, that Mussolini will hurry in to share the loot of civilization. We expect to be attacked here ourselves, both from the air and by parachute and air borne troops in the near future, and are getting ready from them. If necessary, we shall continue the war alone and we are not afraid of that. But I trust you realize, Mr. President, that the voice and force of the United States may count for nothing if they are withheld too long. You may have completely subjugated, Nazified Europe established with astonishing swiftness, and the weight may be more than we can bear.”

Churchill, Winston, and Warren F. Kimball. Churchill and Roosevelt – the Complete Correspondence. First ed. Vol. 1. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Pr., 1984. 37-38.

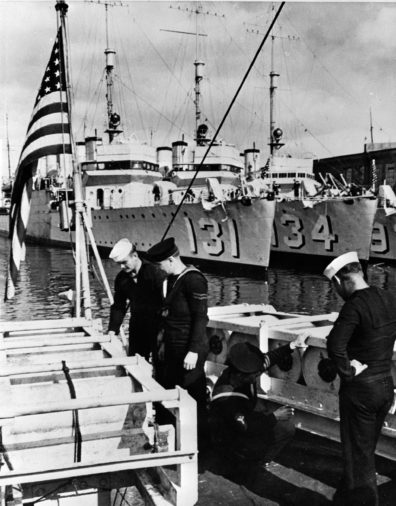

Churchill asked the United States for the loan of “forty or fifty of your older destroyers,” and warned that without them Britain would be unable to fight the “Battle of the Atlantic” against Germany and Italy. The defeat of Britain would be a catastrophe for the United States, leaving it at risk for war on two fronts.

What followed was three-and-a-half months of negotiations. There were significant issues to sort out. President Roosevelt’s initial response was not what Churchill hoped for. Roosevelt responded, “a step of that kind could not be taken except with the specific authorization of Congress and I am not certain that it would be wise for that suggestion to be made to the Congress at this moment.”

Credit: Associated Press. “Churchill dons helmet.” Photograph. New York: World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection c1940. From Library of Congress: Churchill and the Great Republic. http://www.loc.gov/item/2004666450/ (accessed September 2, 2015).

Throughout the rest of May, and into June, Churchill continued to reach out to the United States for assistance. On July 3, 1940, the British Navy bombed the French Navy at its base in northwestern Algeria. Jackson writes about this event in That Man: An Insider Portrait of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Pg 85.

“The specter of overwhelming German naval power, added to her seemingly irresistible air and land forces, deeply troubled the President. If the Germans should capture the French fleet, it – with Germany’s own and that of Italy, and with probable cooperation from Japan – would leave the United States to face alone a most formidable naval and air power. But in the early days of July, Britain, defying what seemed to be forces as inexorable as fate and risking alienation of the French people, boldly attacked and largely disabled the French fleet so that it could no longer be of substantial service to Hitler. Britain won not only our admiration for her courage and audacity but our gratitude as well.”

During the month of August, discussions between Britain and the United States shifted from a loan or sale of the destroyers to an exchange of the destroyers for bases on British territories in the North Atlantic and the Caribbean. Jackson discussed in length the “Destroyer-Bases Exchange” in the oral history he gave to Harlan B. Phillips from Columbia University in 1952-1953. Below is a quote from pages 892-893.

“On the 13th of August, Stimson recites that he, with Knox, Sumner Welles and Henry Morgenthau, met with the President and formulated a proposed agreement — that is, outlined the essential points of an agreement. Sometime before that the President had discussed with me the legal situation as to whether he had authority to make a disposition of these destroyers without further authorization from Congress. On the 15th of August, I had advised him that we, in the Department of Justice, definitely believed that we did have authority to act without the consent of Congress.”

Credit: The Robert H. Jackson Center, International News Photo Collection

Jackson states in his Oral History that, “the opinion contained a simple, statutory interpretation, which if it hadn’t been in the context of war, would not have been even a very important one. It approved the transfer of the destroyers, because they fell in the classification of obsolescent materials, provided the naval and military authorities certified that they were not needful for the defense of the United States. The opinion refused to approve the transfer of the mosquito boats, since they fell in a different classification, and it made no discussion of international law aspects of the transaction.”

The opinion resolved that:

“Accordingly, you are respectfully advised:

(a) That the proposed arrangement may be concluded as an executive agreement, effective without awaiting ratification.

(b) That there is Presidential power to transfer title and possession of the proposed considerations upon certification by appropriate staff officers.

(c) That the dispatch of the so-called “mosquito boats” would constitute a violation of the statute law of the United States, but with that exception there is no legal obstacle to the consummation of the transaction, in accordance, of course, with the applicable provisions of the Neutrality Act as to delivery.”

Jackson’s opinion did not deal with aspects of international law. Later, he would write about his views on international law and the right of neutral countries to extend aid to countries at war in a speech he was scheduled to make at the Inter-America Bar Association in Havana Cuba, March 27, 1941. He was prevented from giving this speech due to a violent storm. The Honorable George S. Messersmith, American Ambassador to Cuba, delivered the speech in his absence.

“Present aggressive wars are civil wars against the international community. Accordingly, as responsible members of that community, we can treat victims of aggression in the same way we treat legitimate governments when there is civil strife and a state of insurgency – that is to say, we are permitted to give to defending governments all the aid we choose.”

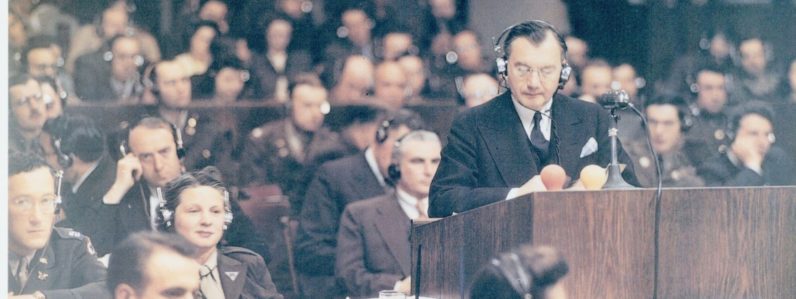

On September 2, 1940, President Roosevelt signed the Destroyers for Bases Agreement. Today, 75 years later, we remember the significant events that happened during the summer of 1940. September 2, 1945, Japan formally surrenders to the Allies, bringing an end to World War II. A few months later, on November 21, 1945, Robert H. Jackson steps to the podium in the Palace of Justice in Germany to give his powerful Opening Statement before the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg.

Credit: United States Office of War Information. Overseas Picture Division, Library of Congress.