ESSENTIAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE REPUBLICAN AND DEMOCRATIC PARTIES (n1)

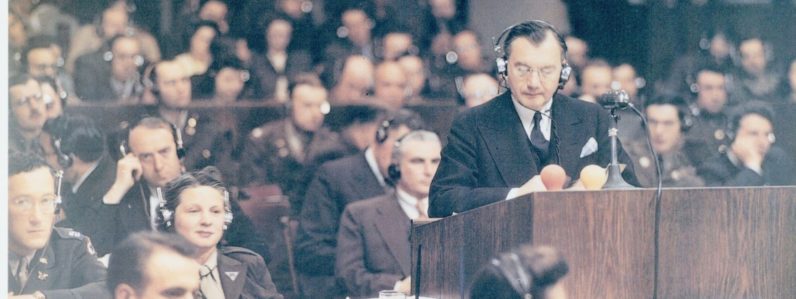

GLENN FRANK AND ROBERT H. JACKSON (n2)

This argument was presented on Thursday evening, April 11, 1940, and was one of the regular Town Hall programs. The moderator of the program was George B. Denny, Jr. Glenn Frank at this time was chairman of the Republican Program Committee and had just sponsored the composition and publication of an extensive Republican Campaign Handbook. The Honorable Robert H. Jackson, not long before appointed Attorney-General of the United States, was widely referred to as President Roosevelt's choice for his successor. As the third term idea gained momentum in April, 1940, Mr. Jackson was frequently mentioned as a possibility for the vice-presidency (even though from Roosevelt's state of New York).

This program was typical of the Town Hall debates-a genuine two-sided argument rather than a "panel discussion" as exemplified in the Chicago Round Table(n3) or as a "symposium discussion" as illustrated in the American Forum of the Air series.(n4) Frank and Jackson were handicapped in the respective debates by reason of the limited time. Each could do little more than to outline his position. Notable is the caution and temperateness with which each addressed both the visible and the listening audiences. Frank attempted to state the underlying philosophy separating the parties rather than to take up specific issues; he attempted without sharp thrusts at the other party, to defend his own group. His defense was almost too apologetic. Jackson, likewise, proceeded without rancor. Cleverly, since he prepared his manuscript in advance and therefore could not directly reply to the preceding speech, he analyzed the "Republican doctrine prepared by Dr. Frank and his battalion of braintrusters, 200 experts strong." Students of American political science will find much interest in deciding whether the differing aims of the parties as given in this debate is an accurate interpretation of those differences.

The real test of these two debaters appeared when the questioning period developed. Each was skillful and direct in his replies. In analysis, argument, citation of evidence, audience adaptation, and persuasiveness Jackson had the slight superiority in the set speeches; Frank ranked higher in language and delivery. In the question period Frank's delivery, cogency of thinking, mastery of language, and extempore ease again gave him an advantage.

In sheer public speaking ability, including thought, language, delivery and related elements, these two participants on this occasion were both "superior." For those skeptics of this period who bemoaned the alleged decline of American parliamentary speaking, reference might well be made to the high platform skill of Frank and Jackson.

Each speaker, obviously, represented an entirely different speaking background and mental approach to an audience. Frank spoke always as an academician and reflected (in a favorable way) his speech training at Northwestern University and his formal platform experiences of many years. Mr. Jackson followed the style of the highly-experienced lawyer, at home not only before turbulent audiences but also before the nine men listening to him from the Supreme Bench at Washington.

Of his training, Mr. Jackson states, "I debated in high school, and have always done a good deal of public speaking as well as pretty constant professional work in court.

"My method of preparation varies with the occasion. If the occasion is a formal one, I prepare a written speech. After outlining it I sometimes dictate it and sometimes write it in long hand. If the occasion is an important one, or the subject matter is of special interest to me, I may rewrite it many times. On such occasions I follow the manuscript very carefully and the text to be printed represents exactly what I said, except that I sometimes make informal introductory remarks in response to something that has previously occurred on the program. On informal occasions my preparation consists of notes which are followed as a general outline. I have never written an argument to be made in court, but always made careful preparation of notes to make quite certain that nothing in the excitement of the moment would be over-looked. The only advice that I can give to young speakers is as old as the hills. Certainly no one ought to attempt to speak on a subject unless he has given it careful study so that his words would carry some authority. I know of nothing that would increase one's self confidence and improve his presentation like a thorough knowledge of the subject.

"I am one who believes that public speaking is no less important now than formerly. Techniques must be changed to meet new conditions such as the radio and the amplifier. Certainly there has been no decrease in the influence of a sincere and earnest personality which can best be sensed by the actual presence of the speaker."(n5)

America's Town Hall of the Air has now completed its fifth season, in cooperation with the National Broadcasting Company, from the Town Hall, New York. Millions of listeners tune in each week and hundreds of discussion groups throughout the nation function under the direction of the Town Hall directors. See the Thompson-Nye debate in Representative American Speeches: 1937-1938, and the Eastman argument, in Representative American Speeches: 1938-1939.

MODERATOR DENNY: Good evening, neighbors. It is frequently said nowadays that the 1940 elections will be the most important held in this country since the Civil War. Certainly American interest in political, economic, and social questions has never been greater than at this time, and there is probably more intelligent interest in public affairs today than we have ever had before. In any case, the men between-and by that I mean all of those who listen carefully to both sides and cast their votes for the candidates and platforms they believe will serve the best interests of the country-are watching carefully the activities of both parties and appraising their potential candidates and attitudes on public questions. It has been said also that there were times when the choice of the voters on election day was between Tweedledum and Tweedledee. If that is so today we ought to know it. However, if we can judge by some of the speeches made from this platform during the past five years, there is considerable difference of opinion between the Democratic and Republican parties as presently constituted. Certainly we have been fortunate in securing the acceptance of these two speakers, Dr. Glenn Frank, chairman of the Republican Program Committee and therefore an authoritative spokesman of his party and the Honorable Robert H. Jackson, Attorney General of the United States and outstanding spokesman for the present Democratic Administration. We are to hear first from Dr. Frank, whose national reputation as an editor and former president of the University of Wisconsin has been enhanced by his work in his present post. I take pleasure in presenting to you Dr. Glenn Frank.

DR. FRANK: I hope my associate in this discussion, the distinguished Attorney General of the United States, Mr. Jackson, will agree with me that it will be impossible to give much reality to the argument of the evening unless, at the outset, we define our terms so that it will be perfectly dear what both Mr. Jackson and I mean when we refer to the Republican and Democratic parties. We could talk about the historic record of these two parties as they have operated under fire when official responsibility has been upon them. We could talk about the traditional philosophies of these two parties, ranging over the policy pronouncements of Hamilton, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Jackson-at least Andrew Jackson. We could, I suspect, give you a fairly colorful evening if we condescended to personalities, historic and contemporary, and centered our attention on isolated episodes, each muckraking the party of the other.

I am not, and I suspect Mr. Jackson is not, interested in any of these approaches to the question: What are the essential differences between the Republican and Democratic parties? I am not interested in any of these approaches because I think they have little, if any, relevance to the political decisions and practical interests of the American people in 1940. In these later years life has laid too heavy a hand upon too many of us, fortune has failed to smile upon too many of us, for me to believe that many Americans will cast their votes in 1940 in terms of the history of our two parties. Few emotions will be stirred in 1940 by obsolete slogans or by the waving of faded battle flags woven out of the issues of other generations. Men without a job, staggering under unbearable debt, with their backs bending under a back-breaking taxation, women watching the loss of their homes, youth staring at doors of opportunity barricaded by the sluggishness of the nation's enterprise are not going to spend much time raking over the ashes and embers of political history.

And the fact is that, traditionally, save for variations of emphasis in this decade or that, there have been no essential differences between the Republican and Democratic parties in their political and economic philosophy. Variations, yes, but, in essence, both have grounded their governing upon a political philosophy of democratic self-government under the check and counter-check of distributed and balanced powers, an economic philosophy of private enterprise under the minimum governmental regulation necessary to prevent abuse and promote justice in its operation, and, if I may use the term in this connection, a spiritual philosophy of civil liberties under which freedom to think, to write, to speak, to petition, to worship, to participate in political opposition to the party in power have been supposed to be secure from denial, from vindictive harassment or assault even by government. I used to think this longstanding similarity of our two parties was to be deplored. I do not any longer. More mature consideration has convinced me that it is impossible to operate a great nation, with anything like a stabilized well-being, through a two-party system, unless the two parties are in essential agreement on what the nature of both the political system and the economic system of the country should be. If the two-party system is made up of two parties whose political and economic philosophies are at opposite poles, every election overturn becomes, in effect, a revolution, and the whole national enterprise is disrupted, thrown out of gear, and, for a run of years at least, shrouded with a depressing shadow of uncertainty.

No effective light would be thrown on the immediate importance of the question we are discussing if Mr. Jackson and I attempted to muckrake each other's parties. Both parties, being made up of human beings, have had their share of great statesmen and crooks; both have had their phases of high advance and low retreat; both have, at one time and another, served the many and been exploited by the few; both, at varying levels of local and state and national administration, have had their share of scandals and superb service.

No. The only question of difference worth discussing is the difference between the policy and action followed by the New Deal Administration during the last seven years and the policy and action a Republican administration would be likely to follow if the fortunes of balloting returned the Republicans to power next November. You may say that is hardly a fair way to state the question, because, you may say, judgment on the New Deal can be based on a record, while judgment on the probable policy and action of an incoming Republican administration must be in the nature of a prophecy, and that such prophecy, made in advance of the platform the Republicans will draft and the candidate they will nominate at Philadelphia next June, can be only a guess. How can anyone know, you may ask, what forces will draft the platform or what behind-the-scenes deals will dictate the leadership at Philadelphia? Ordinarily, respecting any party, both this observation and this question would be valid.

But I speak with a feeling of unusual certainty tonight about the probable program and probable leadership-I mean about the nature of the program and leadership-of 1940 Republicanism because I am not basing my judgment on a guess about forces that will operate in the Philadelphia convention or about deals that might be attempted. I base my judgment upon a firsthand knowledge of what the rank and file of Republicans are thinking and feeling today. And what the rank and file of Republicans are thinking and feeling is today more important than what any individual Republican leader, old or new, is thinking. I think I know what is today moving in the minds and hearts of the mine-run of Republicans from coast to coast. I think I know because I am one of them. And then, for the last two years, I have been at an unusual listening post. As chairman of the Republican Program Committee, which has carried out one of the most comprehensive soundings of party beliefs and determinations in the history of American politics, I have had the chance to eavesdrop the minds and hearts of thousands upon thousands of rank-and-file Republicans throughout the nation. Unless my hearing has been bad, I know what these rank-and-file Republicans are saying among themselves. And if there is a spirit of blind reaction in the rank-and-file Republicanism of this country, I have been unable to find it with a dragnet of research and referendum in these last two years.

The rank-and-file Republicans of this country, as I have come to know them in these two years, are not hide-bound. Neither, thank God, are they harebrained. They are generally and justifiably skeptical of political medicine men with their quick and quack remedies. They do not belong to the decay school of thought which has captured so many of the official liberals of the moment. These rank-and-file Republicans simply do not believe the assumption now current in some New Deal quarters that the America we have known-the America of political liberty and private enterprise-is a dying America except as the political pulmotor of the Federal Government can keep it breathing. They believe, not as wishful thinking but in light of obvious fact, that American enterprise can expand more, offer more investment opportunity for savings, provide more jobs for workers in factories and on farms, create more profitable outlets for the energies and genius of the people, and lift living standards immeasurably higher in the next twenty-five years than in the twenty-five years before 1929, if too many hurdles are not thrown in its way by either the public policies of government or the private policies of business. These rank-and-file Republicans do not believe that the ranks of businessmen, industrialists, and bankers are devoid of intelligence, competence, and social sensitiveness. They do not think the political genius of the nation has gone bankrupt so far that it must be placed under a receivership of appointed administrators. They believe that there is a vast fund of leadership in the nation that suffers neither from the rigor mortis of reaction nor from the St. Vitus's dance of irresponsible utopianism. And they believe it is the business of the Philadelphia convention to find such leadership so that they--the rank-and-file Republicans of 1940--can follow it and help it lift the standards around which the stable intelligence, effective competence, and sound social sense of Americans who believe in democratic self-government and an intelligently modernized economy of private enterprise can rally.

This rank-and-file Republicanism is not a do-nothing Republicanism. It is not allowing either vested interests or vested ideas to obscure its understanding of those social and economic needs to which political policy must today be vitally related or meet deserved rejection at the hands of an enlightened people. It does not want to repeal a single law that has actually restored or strengthened values. It does not want to repeal any tax the revenue from which is actually needed for essential services-unless it is a tax that is hampering that expansion of enterprise upon which the future of every desirable social service of government depends. It does not wad the Government to wash its hands of concern with the future of agriculture. It does not want to see labor face management without the full advantage of equal bargaining power. It does not want to see homeowners pay exorbitant interest rates or lose their homes. It does not want to see a single American go hungry or houseless or cold. It does not want to see government relax, but rather redouble, effort in behalf of the unemployed. It does not want to see children enslaved in factory or field or mine. It does not want to see the country subject to the manipulations of dishonest speculators. It does not want to delay, by so much as one unnecessary hour, the utmost feasible security for the aged. It does not want to sabotage any intelligent attempt to raise the standards of health and education.

The rank-and-file Republicanism of 1940 is an eager, alert, socially sensitive, progressive Republicanism. If it throws itself in opposition to hastily conceived, wastefully financed, and incompetently administered policies pursued in the name of these sound social purposes I have just listed, it is because the rank-and- file Republicanism of 1940 does not believe that political leadership has done a thing just because it has said it. An unsound procedure can defeat a sound purpose it seeks to advance. The New Deal leadership said in 1933 that what the people wanted was action; 1940 Republicanism insists that what the people now want is results. If this rank-and-file Republicanism of 1940 displays a friendliness to policies designed to hasten the growth of American enterprise, it is not because this Republicanism is the tool of dark and sinister interests, but simply because it is practical enough to know that unless the business, the industry, and the agriculture of the country are made and kept going concerns, even the soundest social advances of modern government will sooner or later be wiped out.

This rank-and-file Republicanism-not the picture which an elaborate and sustained attempt to smear the Republican Party as a party of reaction has sought to paint-is the Republican Party in 1940. I say that with confidence because in the last two years I have felt the power of its determination, and any leadership that would attempt to thwart it, and any leadership that fails faithfully to express it, will be broken. Among intelligent Americans in both the Republican and Democratic parties there is not much difference of opinion about the goals toward which we want, as a people, to move and toward which we want government to help us move, but there is a growingly wide and legitimate difference of opinion about what policies will and what policies will not advance us toward these goals.

MODERATOR DENNY: Thank you, Dr. Frank. One of the most distinguished members of the present Democratic Administration is the Attorney General of the United States, formerly an attorney of Jamestown, New York, and successively Assistant Attorney General and Solicitor General-an eminent Democrat. I take pleasure in welcoming back to the Town Hall platform the Honorable Robert H. Jackson.

MR. JACKSON: Since the subject for tonight was chosen, world events have made the differences between us Americans seem trivial beside those deep differences of system and culture that men are dying for abroad. We, Dr. Frank, may be grateful that our differences are only those which can be settled at the ballot box, and while we differ in detail, we have no disagreement in wanting to continue the fundamental principles of our government and of our society. In fact, Dr. Frank and I agree on too many points to make a real jolly evening for you.

Before the New Deal, there was frequent complaint by thoughtful people, some liberal and some conservative, that there was no real difference between the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. Since the Democratic Party has been under the leadership of President Roosevelt, that complaint has been less frequent. Nearly every partisan Democrat and nearly every partisan Republican agree that there are fundamental differences between the Democratic Party and the Republican opposition. But it is difficult to get them to agree on a statement of those fundamental differences.

If a man from Mars should examine the New Deal record and then read the modernized statement of Republican doctrine prepared by Dr. Frank and his battalion of brain-trusters, 200 experts strong, he might conclude that Dr. Frank's work was a defense of the Roosevelt record. Certainly he would conclude that most of the ideas discussed by Dr. Frank came from President Roosevelt. The Republican program of Dr. Frank accepts, in principle, minimum-wage and maximum-hour legislation, Federal subsidies to agriculture, soil conservation, a housing program, the elimination of tax-exempt securities, the regulation of stock markets, securities issues, and public utilities, and even government competition, to some extent, in the power industry. It favors such bitterly contested policies as collective bargaining for labor, reciprocal trade agreements, relief for the unemployed, and a social security program. It is content if the budget is balanced not before the election of 1942, and is content if we return to a fixed gold standard at some indefinite date.

There are, to be sure, guarded suggestions in the report that the New Deal record is not perfect and that much remains to be done to satisfy the promise of American life. But such criticisms are on the whole more tempered than many that I have heard from New Dealers. There is nothing in the Glenn Frank document that suggests a fundamental difference in objective or approach from Mr. Roosevelt. Our man from Mars might well wonder whether the Republican brain-trusters could find a better leader to fight for their principles in 1940 than Franklin D. Roosevelt.

I do not want to give an exaggerated impression of the wholeheartedness of the committee's endorsement of the New Deal. There are plenty of hedge clauses in the report, which can be cited to convince reactionaries and contributors that the road back to "normalcy" has not been cut off. One of the most forceful illustrations is the proposal to return to the Mellon system of taxation. Every tax imposes some economic burden on those who pay it. The historic position of the Democratic Party is that this burden should be placed where it can most easily be carried, and that taxes should increase in proportion to ability to pay. In regard to this, although it advocates budget balancing, Dr. Frank's report proposes to lower the taxes on the higher incomes. It proposes the repeal of the capital stock tax, repeal of the excess profits tax, and repeal of the normal tax on dividends. It is very significant that not a single proposal is made to lighten the burden of the income tax or any other tax on wages, salaries, or earned income. The only tax relief proposed is to those who are living from investments rather than on their services to society.

A similarly reactionary position is taken with respect to government help to provide relief and work for the unemployed. The committee proposes to the largest extent feasible to take this burden from the Federal Government, which can tax incomes and inheritances, and place it on local governments, which can effectively tax nothing much but real estate and retail sales. The people cannot and should not stand for more sales taxes, and real estate taxes have already been carried to the breaking point for the poor and the middle-class homeowners. To put the cost of relief on real estate means to end relief. Even under our present system, the Republican-governed state of Ohio has witnessed relief riots.

A cruel society cannot be a stable society, and I want to live in a stable and peaceable order. If our Federal Government ceased to aid the unemployed, the aged, and the farmer, our civilization would become at once the richest and the most cruel in modern history. We must balance our economic system with a purchasing power equivalent to our producing power; also we must boldly face the problem of how to preserve equality of economic opportunity and political democracy in the face of the rising power and influence of great accumulations and combinations of wealth.

The real powers in the Republican Party contend, and I think that they honestly believe, that economic opportunity and security for the great majority of our citizens are unattainable by government effort. They still cherish the belief that government help can be sound and effective only if it trickles down from above and takes the form of tariffs, subsidies, tax relief, and other incentives to those already on the upper scales of the economic ladder. I do not mean, of course, to suggest that there are not many things that government may properly do to energize private enterprise. But there is a difference between those of us who believe that the task of government is to promote the general welfare and those who believe that government should help only those best able to take care of themselves. What, therefore, distinguishes New Deal Democracy from its opponents is that we would use the powers of government in a conscious effort to attain and to distribute a high level of production and prosperity not for a few but for the many.

To understand the differences between the two major parties we must look not only at their words but at their deeds. I am well aware that the promises of statesmen of all parties excel their performance. But it is fair to look at the promises and performances of the Republican Party when it was in power, and the promises and performances of the Democratic Party under President Roosevelt. We find a distinct difference in the approach and attitude of the two major parties toward the Government's responsibility to its people. It may not be easy to state this difference, but it is very real in the minds and the hearts of the voters.

Is it unfair to doubt whether the objectives which the Dr. Frank report accepts in principle represent the real attitude of men who were openly hostile or coldly indifferent when President Roosevelt and his party were struggling to write into law the requirement of truth in the sale of securities, fair play on the stock exchanges, a limitation on the right of super utility holding companies to play with other people's property, the right of workers to bargain collectively, the provision of jobs instead of a dole for the unemployed, the right to unemployment and to old age insurance? Is it unfair to ask when and for what reason those who bitterly opposed, or grudgingly accepted, these great reforms decided that they want to improve them, extend them, and administer them better? If the Republicans now concede these principles to be sound and wise, why has President Roosevelt's effort to put them into practical effect won him such deep and lasting hatreds from the financial backers of the Republican Party?

Dr. Frank's report does not sharpen or define these real underlying issues between the two parties as now constituted and led. It is to be feared that the party platforms, if they are made up of the usual timid generalities, will also fail to disclose their really opposite objectives. The intuition of the people will sense the difference better than it can be stated. President Roosevelt has more than once warned against the smooth evasions of the real issues which say to us:

Of course we believe all these things; we believe in social security; we believe in work for the unemployed; we believe in saving homes. Cross our hearts and hope to die, we believe in all these things; but we do not like the way the present Administration is doing them. Just turn them over to us. We will do all of them-we will do more of them-we will do them better; and, most important of all, the doing of them will not cost anybody anything.

The next Administration may deal with severe tensions in our society. Its dominant task will be to reexamine governmental policies in the light of our experience. We must complete a long-term program to take the place of short-term remedies and emergency experiments. Although we stand aside from the European conflict, our economy, our social life, and our thinking will not escape its far-reaching effects. Victory will bring prestige to the ideas and the systems and the doctrines of the successful country. We must face the peace of Europe, which may test our stability even more than the war of Europe. We do not know what modifications of their way of life and what reorganization of their economy even the democracies of Europe may make in order to win the war. Ideas or practices that bring victory will exert new pressures. In this competition of ideas and loyalties our system of representative democracy has belatedly undertaken to provide economic opportunity and security for all of our people. There is no wisdom in turning back. There is no time to waste. It is later than you think.

MODERATOR DENNY: Thank you, Mr. Jackson. . . . Now we are ready for our question period. Questions, please.

MAN: Dr. Frank, from past experience, many of us have good reason to doubt the Republican platforms. I would like to ask you specifically: If the Republicans get in, in 1940, what will be their attitude toward the Wages and Hours Law?

DR. FRANK: I can only give you the attitude taken by the Republican Program Committee, since the Republican program hasn't yet been written. It will be written in Philadelphia in June. The attitude of the committee's program report was not in violation of the underlying principle of minimum wages and maximum hours for the protection of those unable to protect themselves through collective bargaining. I have given you my judgment that the process of the Program Committee is an accurate reflection of the rank-and-file sentiment and point of view which, in my judgment, will dominate in color the policy of the Republican Party both during the campaign and after the election.

MAN: Dr. Frank, you spoke at great length about a new and intelligent political and economic outlook of the rank-and-file Republican. Will you be kind enough to advise since when, if ever, have the rank-and-file Republicans chosen presidential candidates at a national convention?

DR. FRANK: Again, that is of a piece with the answer I made in part on the wages-and-hours question. During the last two years the Republican Party has been engaged in an extensive process of thoroughly democratizing one of the most important party processes, namely, the formulation of policy, and doing it at a time when the Democratic Party's process of policymaking has been becoming increasingly autocratic and centralized.

MAN: Mr. Jackson, is it not true that during the application of the so-called Mellon tax schedules, running lower on high-income tax returns, more money was taken in those higher brackets in tax collections than was taken in under the higher taxes before that and the higher taxes today on those incomes?

MR. JACKSON: Regarding the question about the amount, I haven't the figures in mind; but of course the net collections of the Government depend not merely on the rate but upon the number of people who enjoy those incomes. There were more people who enjoyed, or thought they enjoyed, those incomes in 1929 and those years before, and reported on that basis. I don't think that you can successfully contend that a low rate will produce more income for the Government if you apply it to the same base. You are comparing two different eras, and applying to them two different bases.

MAN: Dr. Frank, do you think that the statement that "that government which governs least governs best" is applicable to America in 1940; and if not, what extensions of the Federal Government in the past seven years have been justifiable?

MODERATOR DENNY: Let's take the first part of that question first. We will leave off the last one; that is too long.

DR. FRANK: I do not believe that the bald statement that the government which governs least is the best government applies to the complicated and interdependent situation of 1940 in this or any other modern civilization.

MAN: Mr. Jackson, don't you think that one of the prime differences between the Republican and Democratic parties is that the Democratic Party, in its administrations, promulgates various pieces of progressive legislation that seem radical at the moment, and then, when its terms are up, the Republicans come in and mellow and sanctify this legislation?

MODERATOR DENNY: I take it that the questioner is a Democrat, Mr. Jackson.

MR. JACKSON: I welcome him as such, and I endorse his statement.

MAN: Dr. Frank, you don't see very many essential differences between the two parties, but don't you find in the statements of the Honorable Mr. Jackson as to the performance of the Republican Party in Congress, where it has tried to nullify the efforts of the Democratic Party along progressive lines, an essential difference right there?

DR. FRANK: As one of the mellowers and sanctifiers, in short, as a Republican, I would be perfectly happy to have someone who knew the details make a detailed comparison between the cordial cooperation of the Republican forces, under the New Deal, with valid progressive legislation, and the obstructive forces of the Democratic element in the Congress when the Hoover Administration-which has been so heartily maligned by the New Deal leadership was undertaking to advance highly progressive legislation on many fronts, and it was impossible to get through a Democratically controlled House even progressive banking legislation.

MODERATOR DENNY: I recognize a distinguished Republican in the audience who is about to ask a question, Mrs. Preston Davie.

MRS. DAVIE: Mr. Jackson, I would like to ask you how the New Deal, if it gets in, proposes to re-employ the 11,000,000 unemployed, if it continues with its punitive policy toward business and the harassment of business?

JACKSON: There has been no punitive policy toward business. There has been a distinct effort to curtail some kinds of business in the interests of other kinds of business. The Federal Trade Commission acts on a complaint by some businessmen that other businessmen are being unfair to it. Every suit that has been instituted by the Department of Justice against business groups has been instituted at the request and upon the complaint of other groups of businessmen who claimed they were being ruined. Government must arbitrate those differences and must take a position in reference to those groups.

MAN: I should like to address my question to both speakers. In the light of recent foreign developments, do you think America should continue to purchase gold from foreign countries so as to create purchasing power in those foreign countries and thus aid our foreign export trade?

DR. FRANK: Now we are getting over into the field of money. When we get there, I am in exactly the same position that the monetary experts are: I don't know a single thing about it, except instead of saying, "Should we continue to buy the gold?" I think it would have been far better if we hadn't bought as much as we have.

MODERATOR DENNY: Mr. Jackson, do you know anything about money?

MR. JACKSON: It is very apparent that that isn't one of the differences between Dr. Frank and myself.

MAN: I would like to ask each speaker to answer this question. First, Mr. Jackson: What new plans, if any, has the present Administration to put to work the idle money in this nation?

MR. JACKSON: The Administration has had a problem of attempting to raise the purchasing power of the people in the lower income groups, who are the great purchasers of the nation. Those are the groups that spend their money. If you recall, when the depression hit the motor industry, one of the explanations which was given was that there was no longer ability to dispose of used cars, and used cars are the product which are sold to people of low incomes. It is the belief of the group that if you can restore purchasing power so that business has customers, the idle money will go to work supplying the needs of those customers, and that primarily the reason why business is down is because customers aren't available to buy its goods.

MODERATOR DENNY: NOW, Dr. Frank, will you comment on that same question?

DR. FRANK: Thanks to Mr. Jackson for dramatizing at least one very profound difference between the Democratic and Republican parties today. I agree with Mr. Jackson, and I agree with the most ardent New Dealer that you can't keep this high-powered productive system going without customers who have money in their pockets with which to buy the output of that productive system. But I dissent heartily, as does the Republican Party generally, from the idea that you can create purchasing power adequate to keep this high-powered productive machine going by either government-made work or elaborate government spending of borrowed money. As a very temporary shot in the arm to overcome a serious, acute condition, yes; as a going economic process, no. All the record of the experiment is against it.

MAN: Mr. Jackson, youth wants to know what definite steps your party will take to keep America out of war.

MR. JACKSON: I think the program of the Administration has been made very clear in the legislation which has been proposed by the President and enacted. There has been no indication of a likelihood of our getting into the war, and the legislation is certainly adequate-up to any present needs.

WOMAN: I would like to ask Dr. Frank what proposals the Republican Party has for putting the 11,000,000 unemployed back to work.

DR. FRANK: The question is: What proposals does the Republican Party have for putting the 10,000,000, 11,000,000, or 12,000,000, or whatever the figure is, back to work. Every attitude, every expression of the temper of the Republican leadership, and every policy incorporated in the report of the Republican Program Committee was directed at the target of revitalizing and re-energizing the basic health of American business, industry, and agriculture, on the assumption that only as the organic health of the economic enterprise of this entire nation returns are you going to get a genuine reabsorption of the unemployed into the ranks of the employed. You can't do it on made work unless you want to stabilize the living standards of this people at a markedly lower level and herd them into armament plants or troop them down the streets on made work.

MAN: Mr. Jackson, which of the two major parties has a larger number of lawmakers and politicians who, in order to improve the material and spiritual welfare of the nation, do their educating on obedience? By that I mean, not to the Ten Commandments which are kept on Sunday, but to the laws of the Sabbath which Christ kept on the Seventh Day. . . .

MODERATOR DENNY: We will take that question for a statement.

MAN: Dr. Frank, I understand that some of the men of the Republican National Committee are directors or controllers of steel corporations who bought large quantities of tear gas and other weapons-

MODERATOR DENNY: I am sorry. That question is out. It is in the nature of a personal question.

MAN: Dr. Frank, you mentioned President Hoover a moment ago. Do you have any idea what his reaction has been to your report? I have seen reports that he is opposed to it.

DR. FRANK: I can answer that question. Mr. Hoover was a member of the committee cooperating in the drafting of the report, and the last time I heard him refer to it, he said he felt it was an excellent expression of the political, social, and economic principles in which he had believed, and which he had preached for the last twenty years.

MAN: I would like to ask one question of each gentleman. Mr. Jackson, do you or do you not believe that the existence of a national deficit of $40,000,000,000 plus is a national peril?

MR. JACKSON: To be perfectly frank with you, I don't know. I have read a great deal that has been written on both sides of the subject. Whether it is a peril, I can't answer. It doesn't seem to me that a deficit created to feed our own people, a deficit for public works which are created in this country—such as schoolhouses and public-works projects throughout the land--can bankrupt us.

MODERATOR DENNY: The same question, Dr. Frank.

DR. FRANK: You mean a national debt of $40,000,000,000? First, let me make clear the spirit in which I say this, and the grounds on which I say it, and about three sentences will state those grounds. I do not say that potentially this economic system of ours can't stand up under a national debt of $40,000,000,000 or even $50,000,000,000; but I do say that a national debt that has jumped, that has virtually doubled in seven years, is symptomatic of a political and economic philosophy which, if given its head, will land the nation in bankruptcy because of the policies that create that large debt.

MAN: After having heard the talk on both sides, as to the very few differences between the Democratic and the Republican parties, I wish to ask Mr. Jackson if he doesn't think the Republican Party could run on the last Democratic platform that was ever written-in 1932-better than the present New Deal party?

MR. JACKSON: I think they not only should run on the platform of the Democratic Party, but they should endorse its candidate, if they feel as they say they do.

MAN: I understood you to say, Mr. Jackson, that the New Deal policies were calculated to tax those who lived on their investments rather than upon their services to society.

MR. JACKSON: I did not say that.

SAME MAN: Well, I am glad to hear that.

MR. JACKSON: I said that the reduction of taxes proposed by the Republicans was entirely directed to the benefit of those who live on investments and had no effect on those who live on wages, salaries, or earned income.

SAME MAN: On that statement, may I ask you a question, in all friendliness to you, in order that the record may be clear? Would you say, then, that it is a Democratic philosophy, or a philosophy of the Democratic Party, that the providing of capitalistic forces of production that come from investments and dividends is not a service to society?

MR. JACKSON: No, I didn't say that-- don't intend to be understood as having said that. But what I do say is that when you have reached the point where you are living on the return from invested capital, it evidences an ability to pay, and that that is a proper element to take into consideration in fixing the tax rate; that the progressive tax should apply according to ability to pay, graduated according to income.

MAN: Dr. Frank, do you know Mr. Landon's reaction to your committee's report ?

DR. FRANK: Mr. Landon gave his hearty approval to this report in a public statement about forty-eight hours after it was issued.

MODERATOR DENNY: Thank you. Dr. Bestor has a question from a listener out of town.

DR. BESTOR: Mr. Jackson, on the issues of foreign policy, what are the major differences between the Republican and Democratic parties ?

MR. JACKSON: I couldn't answer that because I can't find out what the foreign policy of the Republican Party is. Not only are there differences between its candidates, but its candidates sometimes have different policies when they are speaking in different parts of the country. I don't think it is feasible or practical to draw a comparison between a policy which is in effect under the present Administration and the hypothetical policies of hypothetical candidates drawn from a variety of speeches under a variety of circumstances with no continuity and no consistency among them.

MODERATOR DENNY: Dr. Frank, will you speak on the same question?

DR. FRANK: Again, I am speaking tonight very dogmatically about Republican policy because of my two years' experience of intimate contact with thousands and thousands of rank-and-file Republicans whose judgment I know is going to prevail ultimately in the Republican Party, regardless of what any individual leader may say, think, or do. I am as much at sea as to where the foreign policy of the New Deal is really headed as Mr. Jackson is about what the foreign policy of the Republican Party is. If I had to say it in about three or four sentences, I would say that the demand coming up from the rank and file of the Republicans to the leadership of the Republican Party is: First of all, keep this nation out of the wars of Europe. Second, realize, nevertheless, that this is an interdependent world economically and culturally, and you must go to the extreme limit of cooperation in making possible the easiest possible flow of trade and services across the frontiers of the world, provided in the doing of it you don't have to sell out the living standards of American workers and American farmers.

MAN: Dr. Frank, how do you reconcile the following essential differences in the situation, that are paradoxical? In 1938, President Roosevelt, in speaking before a group of women representing national associations, said that to help recovery they should "buy patriotically." In 1939, President Roosevelt, in speaking before a large group of newspapermen, held up a can of Argentine beef and advocated that the American Navy buy Argentine beef because it was cheaper.

MODERATOR DENNY: You are asked to verify President Roosevelt's two apparently inconsistent remarks, Dr. Frank.

DR. FRANK: In the spirit of good manners and sportsmanship, I am going to "pass the beef" to Mr. Jackson.

MODERATOR DENNY: Mr. Jackson "passes the beef" back to the audience, and we will take the next question.

MAN: Dr. Frank, I wonder whether your insistence on the rank-and-file attitude of the Republican Party means that you think the rank and file of the Republican Party will demand and obtain better leadership than any that has heretofore appeared in the Republican Party?

DR. FRANK: No, I do not. I am not here to apologize for the leadership of the Republican Party in the past, because the cold historic record is that most of the political, social, and economic progress that America has made in the last half century has been made under Republican leadership.

MAN: Dr. Frank, almost every Republican Senator voted against the extension of the reciprocal trade agreements. Is that the rank-and-file opinion of the Republican Party?

DR. FRANK: I don't think the rank-and-file sentiment of the Republican Party is a blind, blanket, thumbsdown on the technique of reciprocal trade agreements. I am not taking about any special one. I think the majority of Republicans in this country are skeptical of the handing over of too much unchecked and unreviewed power to administrators. But they have had such a dose of that in the last seven years that you can forgive them.

MODERATOR DENNY: Thank you, Dr. Frank. And with your remarks, we bring to a close the twenty-seventh and final broadcast of the 1939-40 season.

n1) Reprinted from Town Meeting, Bulletin of America’s Town Meeting of the Air. 5:no.27: April 15. 1940. Published by Columbia University Press, 2960 Broadway, New York. (Single copies, ten cents: subscriptions to volume $2.50.) By permission of the speakers and by special arrangement with Town Hall, Inc. and Columbia University Press.

n2) For biographical sketches see Appendix.

n3) See Representative American Speeches: 1939-1940. p. 191.

n4) See Representative American Speeches: 1939-1940. p. 86.

n5) Letter to the author. May 9, 1940.