THE .CHALLENGE OF INTERNATIONAL LAWLESSNESS:~~

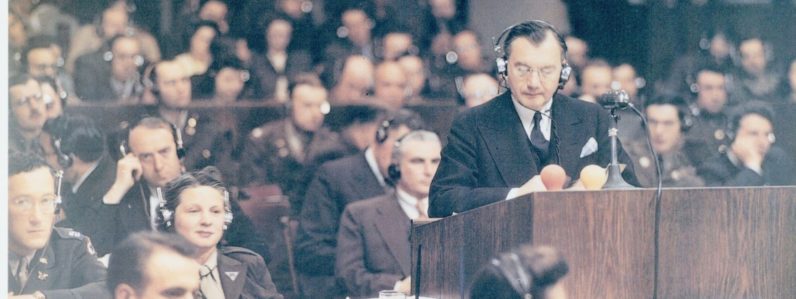

By ROBERT H. JACKSON

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

We lawyers would commit only a pardonable larceny if we should appropriate as affirmation of the ideals of the legal profession a prayer from ancient liturgy:

…Grant us grace fearlessly to contend against evil, and to make no peace with oppression; and, that we may reverently use our freedom, help us to employ it in the maintenance of justice among men and nations…

As men experienced in the conduct of legal institutions which, among men, have largely displaced violence by adjudication, we should have some practical competence in measures to maintain justice among nations.

The Roosevelt- Churchill conference has directed discussion toward the implications of the war in terms of peace. But our people are still thinking cynically of all peace plans, for they feel frustrated and aggrieved at the interruption of a peace they had thought to be permanent. At the end of the World War our people divided into a group who were sure war was ended, because a war to end war had resulted in a fairly comprehensive organization of world powers, and an opposing group who were confident that they had assured our peace by keeping the United States out of it. Now, both awaken in disillusionment- the one to find the world not so well organized for peace as they had believed, and the other to find the United States not so well isolated from war as they had supposed.

I share the public disappointment at the renewal of war as a means of settling the problems of Europe, because I also shared some of the choice illusions of my time. But I cannot let faith be crushed, although the law of the jungle tarries long among nations and achievement of an international order based on reason and justice even now seems remote. The history of our experience with the slow but solid evolution of domestic law keeps me from expecting miracles on the one hand and from becoming cynical, on the other.

Wheeler's would commit only a pardonable larceny if we should appropriate as an affirmation of the ideals of the legal profession of prayer from ancient letter G Grand Theft Grace peerlessly to contend against evolve in to make no peace with depression and that we may reverently use our freedom help us to employ it and maintenance of justice among men and Nations police sirens by judication we should have some practical competence and measures to maintain justice among nations the Roosevelt Hotel Conference has directed discussion towards the implications of the war in terms of teeth that are people are still singing cynically of all peace plan for they feel frustrated and believe that the interruption of a peace they have thought to be permanent at the end of World War I didn't to a group who were sure war was ended because of war to end War had the Salted and a fairly comprehensive organization of Fawlty Towers I need a popping group who are confident if they had a shirt are Peace by keeping the United States out of it now both awaken and disillusionment the one to find the world not so organized herpes if they had believed and the other to find the United States not so well isolated from where is they had supposed to sit at the renewal of a war as a means of settling the problems of Europe because I also shared some of the choice illusions of my tongue but I cannot let food be crushed although the law of the Jungle Terry's long of Nations and achievement of an international order based on reason and Justice even now see them out history about experience with a slow but solid evolution of domestic law keeps me from expecting miracles on the one hand and two becoming cynical on the other.

Stability of International Law

The fact is that under today’s political and economic chaos there is actually functioning a relatively stable body of customary and conventional international law as a foundation on which the future may build. Lodged deeply in the culture of the world, unaffected by the transitory political structures above it, is a bedrock belief in a system of high law. Entrenched dictators spend no end of effort to persuade their own people that they are not lawbreakers and to rationalize their policies for a law-conscious public opinion. Not one of them today would dare to boast, as did Con Bethman Holweg at the opening of the World War, that he is violating International Law.

Treaties, except some of the great political ones are contrary to a general impression, still usually applied; prisoners of War are being treated pretty generally in accordance with treaty stipulations; there are few, if any, allegations that the sick and wounded are not being treated in accordance with the Geneva Red Cross convention. Foreign offices of all nations in protesting actions thought to be in violation of customary international law or treaty Provisions, pay tactic recognition to the existence and validity of a standard of conduct higher than the transient will of officials. Various departments of the government, in addition to the Department of State, have added international law scholars their staffs; legal arguments are steadily exchanged between foreign offices concerning international disputes, many of which are still decided on this basis.

Diplomats, together with embassies and legations, are still accorded their proper immunities, and Axis diplomats and consuls are being sent home as personae non gratae for overstepping the bounds of their privileges.

Our nationals abroad are still protected; aliens still generally have the benefit of the international rules respecting them; criminals are extradited pursuant to treaty; prize courts still function under international rules and in the domestic courts of the United States, as well as of the other principal powers of the world, pleas are still made to internal law and decisions are rendered in accordance with its principles.

Moreover, new concepts are competing for recognition; war is being waged today, not only in self-defense but upon the ground that aggressors are lawbreakers and outlaws; international sanctions are being applied; assets which would otherwise fall into the hands of aggressors are being frozen; commerce is being protected on the high seas against their paper blockades; the principle of the freedom of seas is being actively defended; the implication of the principle of self-defense are being clarified; and an enlargement of the heretofore indefinite concept of piracy is perhaps developing.

Existing International Institutions

Passing from substantive law to international institutional we have the League of Nations, its system of mandates, the International Labour Organizational and, last but not least, the Permanent Court of International Justice. Although these do not meet the needs of the world, they have many features that represent solid progress and which I am convinced the world cannot afford to throw away.

The League of Nations, for all of its defects and in spite of all that it has left undone, has had a wholesome influence on the international thought and habit of our time. The Covenant required publicity and registration of treaties, and it authorized recommendations to reconsider treaties which became inapplicable. A more enlightened concept of trusteeship underlies the system of mandates for backward people created by the Covenant. It required mediation, arbitration, or conciliation of certain classes of controversies, and it provided for the establishment of a Permanent Court of International Justice for the adjudication of justiciable controversies. Moreover, the League Covenant, in limiting the right of war, created new obligations of good conduct. It departed sharply from the older doctrine that, in respect of their right to make war, sovereign states were above both the discipline and the judgments of any law, and that their acts of war were to be accepted as legal and just. Instead, for its members it created a category of forbidden and illegal wars- wars of aggression. It made resort to war in violation of the Covenant an act of war against all other members of the League. It provided economic sanctions to be invoked against the aggressor. Even if it was not able to end unlawful wars; it ended the concept that all wars must be accepted by the world as lawful.

Kellogg-Briand Pact

The League, which we rejected, was allowed by the Kellogg-Briand Pact. By it the signatory nations renounced war as an instrument of national policy and agreed that the settlement of all dispute or conflicts of whatever nature or of whatever origin should be sought only by pacific means. While the United States became a party to this treaty, Secretary Kellogg said that it was out of the question to impose any obligation respecting sanctions on the United States. The Senate proceedings make clear that its ratification was due only to the assurance that it provided no specific sanction or commitment to enforce it.

This treaty, however, was not wholly sterile despite the absence of an express legal duty of enforcement. It had legal consequences more substantial than its political ones. It created substantive law of national conduct for its signatories and there resulted a right to enforce it by the general sanctions of international law. The fact that Germany went to war in breach of its treaty discharged our own country from what might otherwise have been regarded as a legal obligation of impartial treatment towards the belligerents.

None Able to Prevent War

Regardless, however, of these juridical consequences, the disillusioning fact is that neither the League nor the Kellogg-Briand Pact proved adequate to prevent war. Whether they did not actually induce a false sense of security which contributed to the undoing of those who relied on their promise is an open question. That a signatory state may lawfully support a war to punish an illegal war may mean merely bigger and better wars. It is a rough international equivalent of the ancient "hue and cry” procedure, which involve the whole community in the troubles of an individual. What we seek is to prevent, not to intensify and spread, wars. And that tranquility can rest only upon an order that will make justice obtainable for peoples as it is now for men.

Our institutions of international cooperation are neither time-tried nor strong, but it is hard to believe that the world would forego some organ of continuous consideration of international problems or scrap what seems to be a workable, if not perfect, pattern of international adjudicative machinery.

Defects of League

It is not difficult with the aid of hindsight to point out structural defects in the League of to complain of the timid use made of such powers as it had. But we can no more dismiss as a failure all international organization because the League did not prevent renewal of war between nations than we can dismiss our federal government as a failure because it did not prevent a war between its constituent states.

Intelligent opinion should not visit upon struggling international instrumentalities that condemnation which rightly may be visited upon the selfishly nationalistic policies of several nations. We must place blame only where there was power. Too many people forget that the League was merely a collective annex of foreign offices. The dependence of the League on the policy of home governments was never better stated than years ago by Sir Arthur Salten:

The League is an instrument through which the real desire of the world for international cooperation can find expression and be put into effect.... But it is not, and cannot be, a shortcut to supreme control. It cannot enable the best part of the world to impose, its will upon a hostile, an indifferent, or an apathetic majority. It is an instrument and not an original source of power. It is a medium, but a medium only, through which the desire of the world can find expression.

Moreover, the League under the Covenant is based upon existing national authorities. The members both of the Council and of the Assembly are nominated by Governments. It therefore expresses the will of the world indirectly, not directly by a parallel form of popular representation. Those who care most for the ideals on which the League was founded can indeed use the League itself in many ways to mobilize and concentrate their forces. But the route to action lies first through the national electorates and the various, national media through which the policy of national Governments can be affected.

The League's position as foreign office subsidiary was probably inevitable, but it was unfortunate for the peace of the world. A diplomat suffers less risk to his personal career if he can hush a delicate issue than if he brings it to the surface and tries to meet it with long-term remedies. The foreign office genius for suppressing issues rather than solving them was the common denominator of all nationalistic representation and became the chief, if not in fact the only, policy of the League.

Sumner Welles, in a really notable address, has aptly said:

The League of Nations, as he (Wilson) conceived it, failed in part because of the blind selfishness of men here in the United States, as well as in other parts of the world; it failed because of its utilization by certain powers primarily to advance their own political and commercial ambitions; but it failed chiefly because of the fact that it was forced to operate, by those who dominated its councils, as a means of maintaining the status quo. It was never enabled to; operate as its chief spokesman had intended, as an elastic and impartial instrument in bringing about peaceful and equitable adjustments between nations as time and circumstance proved necessary.

Some adequate instrumentality must unquestionably be found to achieve such adjustments when the nations of the earth again undertake the task of restoring law and order to a disastrously shaken world.

Need for Flexibility

We now see that such an instrumentality, if it is to compose the world's discord, must have flexibility. Neither maps nor economic advantages nor political systems can be frozen in a treaty. Peace is more than the fossilized remains of an international conclave. It cannot be static in a moving world. Peace must function as a going concern, as a way of life with a dynamic of its own. Unfortunately, however, the internal structure of the League loaded the dice in favor of the perpetuation of the status quo which was also the policy of the dominant powers and the governing classes within them. Any peace that is indissolubly wedded to a status quo- any status quo-is doomed from the beginning. The world will not forego movement, and progress and readjustments as the price of peace. Where there is no escape from the weight of the status quo except war, we will have war. Perhaps if that is the only escape, we should sometimes have war.

The Assembly of the League could advise "reconsideration by members of the League of treaties which have become inapplicable and the consideration of international conditions whose continuance might endanger the peace of the world." That promise to the ear was, however, broken to the hope by the provision that action be only by unanimous consent. Any one dissenting member government could thus perpetuate the status quo, though all the world knew it was at the price of eventual war. This was a fatal situation when the status quo in Europe was an experimental and in some respects an artificial one established by victors in an hour of heat and hate.

Supremacy of Law

The world will not, I trust, be naive enough again to believe it has so reordered its affairs as to prevent conflicts that might provoke wars. The supremacy of domestic law is not based on an absence of individual conflicts. It is predicated on a settlement of them by means that do not violate the peace of the community. The law anticipates a certain amount of wrong conduct, for which it provides damages or punishments. It does not end injustices, but it requires the victims to seek redress through the force of the law, rather than through their own strength.

In this we have to abide the imperfections of legal institutions. I am not convinced, even by my own transfiguration into a Justice of the Supreme Court, that courts have overcome the hazard of wrong decision and of occasional injustice. The triumph of the law is not in always ending conflicts rightly, but in ending them peaceably. And we may be certain that we do less injustice by the worst processes of the law than would be done by the best use of violence. We cannot, await a perfect international tribunal or legislature, before proscribing resort to violence even in case of legitimate grievance. We did not await the perfect court before stopping men from settling their differences with brass knuckles.

But even if we achieve a formula for order under law among all or among a considerable number of like-minded nations, we may as well recognize that its instrumentalities of justice and of adjustment will give, us little security unless we give them a more real support than in the past. There is no dependence on a peace that is everybody's prayer but nobody's business. Peace declarations are no more self-enforcing than are declarations of war. Peace without burdens will no more come to a world that will not assume its risks than domestic peace would come to a community that would not assume the burdens and risks of a force of officers and courts for judging offenders and a form of political organization that commits the physical force of the community to support the peace officer, if necessary.

Law Tested by “the Bad Man"

The American people seem to have believed, some scholars have asserted, that international law operate by the voluntary acceptance on the part of disposed powers. But Mr. Justice Holmes pointed that we cannot test our law by the conduct of the man who probably behaves from moral or social considerations. The test of the efficiency of the law, he is the bad man who cares only for material to himself. Said Holmes:

A man who cares nothing for an ethical rule which is and practiced by his neighbors is likely nevertheless to care! Good deal to avoid being made to pay money, and will want to keep out of jail if he can.

The world is in war today chiefly because its civilization had not been so organized as to impress the "bad man" with the advisability of keeping the peace.

The German people might not have supported a war of Nazi aggression, had there been explicit understanding that it would bring against them array of force they now face. Everything indicates that Hitler's early steps were cautious and tentative and calculated to test out the spirit and solidarity of the rest of the world. Shirer asserts, and we find little reason to doubt, that Hitler was successful in recreating their conscript army in violation of the military provisions if the Treaty of Versailles, only because of default of opposition from the former Allies. He also says that when Hitler sent troops to occupy the demilitarized zone of the Rhineland, in violation of the Locarno Treaty, the troops had strict orders to retreat if the French army opposed them in any way. They were not prepared or equipped to fight a regular army. Peace appears to have been lost, not for the want of a great supporting force, but for the want of only a little supporting force.

Alternative for America

It is in the light of such facts that America will face a tough and fateful decision as to her attitude towards the peace. It is a grave thing to risk the commitments that are indispensable to a system of international justice and collective security. It is an equally grave thing to perpetuate by our inaction an anarchic international condition in which every state may go into war with impunity whenever its interests are thought to be served.

But it is a perilous thing to neglect our own defenses as if we were in a world of real security and at the same time to reject the obligations which right make real security possible. At the end of this war we must either throw the full weight of American influence to the support of an international order based on law, or we must outstrip the world in naval and air, and perhaps in military, force. No reservation to a treaty can let us have our cake and eat it too.

The tragedy and the irony of our present position is that we who would make no commitment to support world peace are making contributions a thousandfold greater to support a world war. We who would not agree to even economic sanctions to discourage infraction of the peace are now imposing those very sanctions against half the world in an effort to turn the fortunes of war.

Roosevelt-Churchill Conference

The Roosevelt-Churchill "Atlantic Charter" promises aid to all "practical measures which will lighten for peace-loving peoples the crushing burden of armaments." Certainly, the present competition, if continued, threatens the financial and Social stability of free governments. Vast standing military establishments and the interests that thrive on them: and the state of mind they engender are no more compatible with liberty in America than they have been in Europe. Five years of the sort of thing the world now witnesses and twenty centuries of civilization will not be worth a tinker's dam.

The Roosevelt-Churchill statement affirms that all nations "must come to the abandonment of the use of force" and it envisions the "establishment of a wider and permanent system of general security." Such happy days wait upon great improvement in our international law and in our organs of international legislation and adjudication. Only by well-considered steps toward closer international cooperation and more certain justice can the sacrifices which we are resolved to make be justified. The conquest of lawlessness and violence among the nations is a challenge to modern legal and political organizing genius.

Men of our tradition will take up the challenge gladly. We have never been able to accept as an ultimate principle the doctrine that, in vital matters of war and peace, each sovereign power must be free of all restraint except the will and conscience of its transitory rulers. Long ago English lawyers rejected lawlessness as a prerogative of the Crown and bound their king by rules of law so that he might not invade the poorest home without a warrant. In the same high tradition our forefathers set up a sovereign nation whose legislative and executive and judicial branches are deprived of legal power to do many things that might encroach upon our freedoms. Our Anglo-American philosophy of political organization denies the concept of arbitrary and unlimited power in any governing body. Hence, we see nothing revolutionary or visionary in the concept of a reign of law, to which sovereign nations will defer, designed to protect the peace of the society of nations.

We, as lawyers, hold fast to the ideal of an international order existing under law and equipped with instrumentalities able and willing to maintain its supremacy, and we renew our dedication to the task of pushing back the frontiers of anarchy and of maintaining justice under the law among men and nations.